#ViRaLfonds in Baden Baden

Of the desire to arrive

What do Hans, Almula, Sepideh, Ingeborg, Katalin, Jutta, Marija and Khalil have in common? From the GDR, Romania, Syria, Iran, Kosovo, Turkey or Erytrea, they all fled from their home and sought refuge in Baden Baden. On January 20th 2019 they stood together on the stage of the city Boenhoeffer Saal and shared their stories with the audience. About 300 people came to one of the two readings organized by the project "Baden-Baden schreibt ein Buch" (Baden-Baden Writes a Book) that we support with our Action Fund ViRaL.

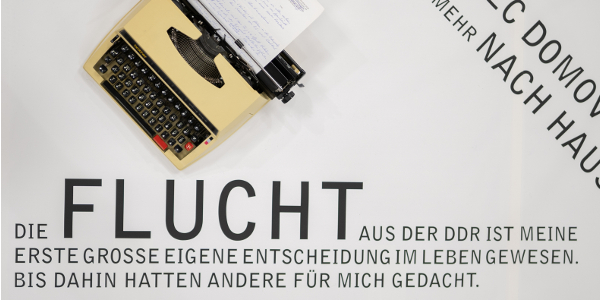

"It was my personal concern to share my story", Hans told me when we talked about his decision to take part in the project "Baden-Baden writes a book" after the event. On 20.01.2019 Hans stood together with Sepideh, Conny, Ingeborg, Jutta, Aida, Perwin, Marija, Katalin, Khalil, Skender, Hatixhe, Midia, Almula, Jutta, Karin, and Eva on the stage of the Boenhoeffer Saal in Baden-Baden and shared his story with the audience. Hans fled the GDR in 1969. Thanks to the help of an unacquainted Dane, he managed to flee to the West via Denmark. Without this stranger, who offered him his help and protection, Hans might not have made it or might have been arrested. Sharing his story seemed important to him today because it can be seen as proof that flight is not a new or strange phenomenon. Since 2015, Hans has been supporting newly arriving refugees in Baden-Baden.

As part of "Baden-Baden schreibt ein Buch" (Baden-Baden Writes a Book), a project of the Stumbling-Stones Working Group in Baden-Baden, organized by Angelika Schindler, Petra Mallwitz and Ulla Hocker, writing workshops are offered to enable people with experience seeking refuge to write their stories. The texts will gradually be published as feature pages in the local newspaper, the Badisches Tagblatt, and will also appear as anthologies.

Most stories have one thing in common: a certain isolation.

All their stories are different. Jutta fled Pomerania as a child in 1945, Hatixhe and Katalin joined their partners. Midia, from Syria, made her way from Turkey to Germany on her own and caught up with her family. Marija fled from her father's violence - a reminder that not only war or political persecution can make an escape necessary. Khalil and Hans fled across the sea - but Hans did not sit in a rubber dinghy. Jutta felt strange in her new school class in South Baden. Perwin finally felt welcome - in Turkey, as a Syrian Kurdish woman, she had not found security in any school and had not been able to attend one for five years.

But most stories have one thing in common: a certain isolation. This often began even before the escape, first through secrecy: many could not tell anyone about their escape plans - not even their parents. Arriving is an important moment, but it does not completely break the isolation. Thus Sepideh says that she feels very comfortable in Baden-Baden, that the gratitude she feels for her freedom and that possibly distinguishes her from the people from Baden, who have lived here all their lives, prevents her from really feeling a part of it. Moreover, she always felt strange with her story. The project has broken the invisibility of many escape stories and the mystery around them. Sepideh says that today she looks differently at the people in Baden-Baden who are strangers to her, and at the city itself.

Their stories will be published in the local newspaper

The stage is opened with a sound installation. The artist Rike Scheffler has cut quotations from the authors and music into a three-dimensional sound work for the six-minute piece "Von dem Wunsch anzukommen". Here you can listen to it.

About 300 people came to one of the two readings on 20 January. Many more people might have gotten to know the stories of the authors thanks to the publication of the articles in the newspaper. The project continues with the work on the book itself, perhaps even beyond. Khalil Khalil outlines a discussion of language - he would like to critically examine terms such as "wave of refugees" or "refugees" in general.

Not all authors could be on stage on 20.01. Some were quite simply prevented for health reasons, but others still didn't feel safe enough in Baden-Baden and didn't consider themselves to have arrived. Some of them feared a negative influence on their still open asylum procedures.